Urbanization

In the first half of the 19th century, when Karankawa Native Americans still lived in the coastal prairie, exiled Acadians were settling the Cajun Prairie area, and the first Europeans began settling the Houston area.

In the 1820s, Stephan F. Austin established the first of several Anglo colonies near the Brazos River where today’s First Colony community in Fort Bend County is situated. In 1836, two New York brothers, Augustus and John Allen, bought more than 6,000 acres near Galveston and began developing the area as an inland port. The confluence of White Oak Bayou and Buffalo Bayou created a natural turning point for boats and made the location ideal as a transportation hub, which they named Houston.

Unfortunately, the flat, marshy prairie—only 50 feet above sea level—was a terrible place to build a town. Settlers and visitors suffered from the mud, flooding, oppressive heat, and mosquitoes, and outbreaks of yellow fever terrorized them and killed hundreds.

Explosive growth

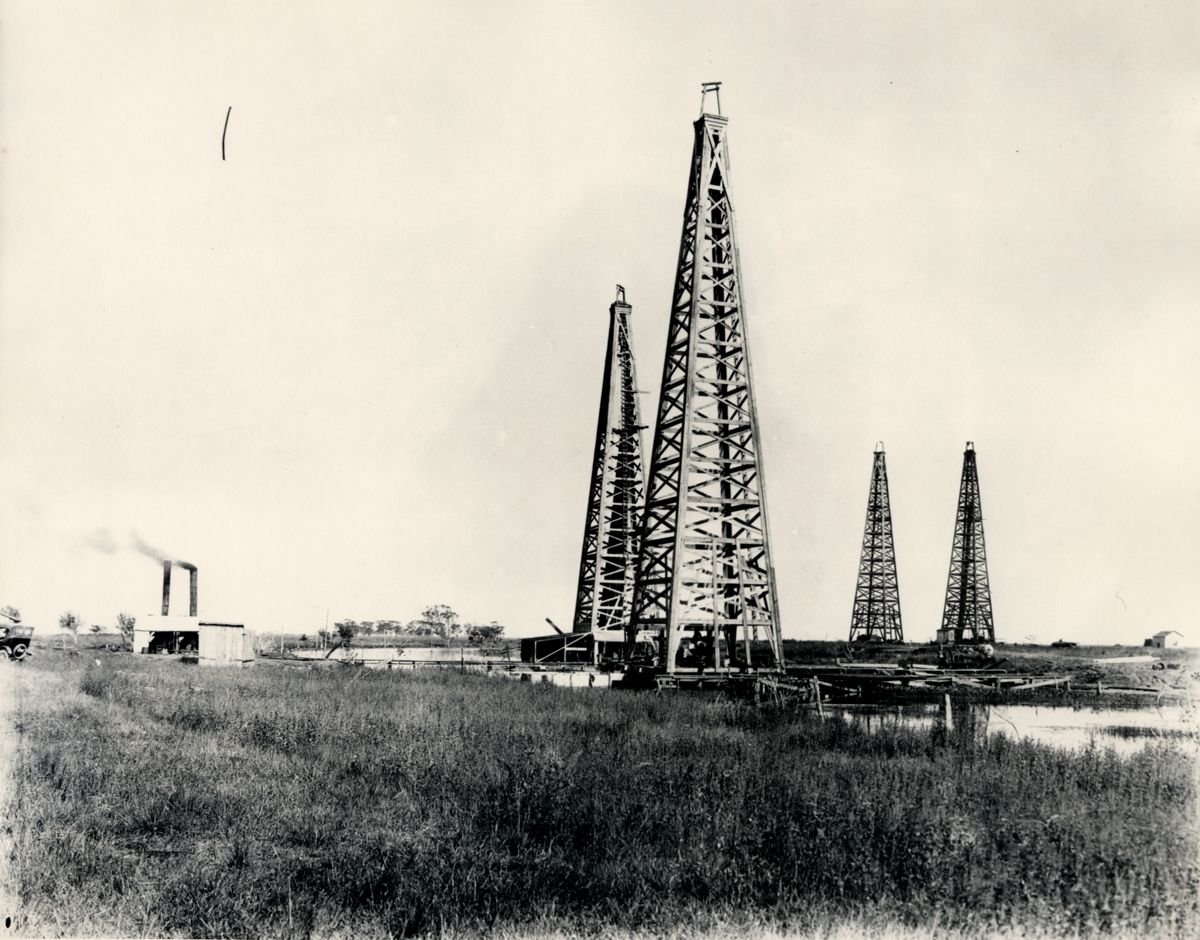

But still the town and area flourished, with settlers gradually fanning out into most of southeast Texas. In Houston, rice was farmed along Brays Bayou and Willow Waterhole Bayou. Cattle were grazed in today’s Brays Oaks area, where Fondren Ranch was eventually established. In 1870, mosquitoes were identified as the source of yellow fever, and mosquito control campaigns began—quarantines, netting, and draining—and the disease began to be eradicated. Houston’s growth really took off. During the 1870s and 1880s, Houston’s cotton and rice industries thrived, supported by the rich, thick topsoil characteristic of the tallgrass prairieland. The modern oil industry began in southeast Texas just a few years later. Houston boomed, housing developments blossomed in the late 1950s, including the Meyerland and Westbury neighborhoods, and industrial and retail construction expanded.

Over time, however, the virgin prairie became overgrazed by cattle, plowed under by farmers, and choked out by invasive species. Suppression of natural fires eliminated even more of the prairie, and urbanization paved and built on much of what was left. During Houston’s 150 years of development, the population expanded from 200 people in 1832, to 2,000 in 1836, 45,000 in 1900, and 1.5 million in 1980. As the city grew, the virgin coastal prairie shrank, as it did nationwide. Today, only 1% of tallgrass prairie remains.

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you got 'til it's gone?

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.

--Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi,” 1970

Flooding continued to plague the area. People eventually grew concerned enough about the destruction of the natural environment and habitats that they realized something drastic had to be done. Environmentalists, governmental agencies, environmental organizations, and private citizens began working together to find ways to mitigate the risk of flooding and to reclaim the region’s native prairie landscapes. One needed change became clear: take better care of the natural environment.

Why are prairies so important?

Prairies support a variety of plants and animals, creating a balanced ecosystem. Restoring and preserving them is crucial for maintaining biodiversity, ensuring sustainable agriculture, and protecting the overall health of our planet. Even prairie remnants are vital for the environment. Here is why.

Prairie underground root systems, which extend 6 to 15 feet underground, absorb water and reduce erosion.

Prairie root systems store up to 3 tons of carbon per acre a year, keeping it there for hundreds of years.

Prairies, like tropical rainforests, act as natural air and water filters.

Prairies boost native ecosystems, aiding native plant growth, supporting pollinators, and providing habitats for diverse species, including those at risk of extinction.

Prairies provide a critically needed habitat for migrating birds, contributing to seed dispersal and pollination by birds and insects.

Prairies offer fertile land for crops and grazing, supporting agriculture and livestock.

Prairies give city dwellers opportunities for recreation, education, and appreciation for nature.